Eugene Onegin

| Eugene Onegin | |

|---|---|

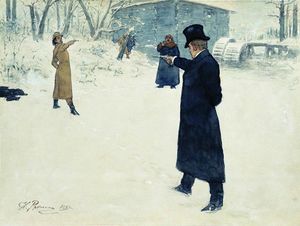

Ilya Repin's depiction of Onegin and Lensky's duel |

|

| Author | Alexander Pushkin |

| Original title | Евгений Онегин |

| Translator | Vladimir Nabokov |

| Country | Russia |

| Language | Russian |

| Genre(s) | Novel, Verse |

| Publication date | 1825-1832 (in serial) & 1833 (single volume) |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

Eugene Onegin (Russian: Евге́ний Оне́гин, BGN/PCGN: Yevgeniy Onegin) is a novel in verse written by Alexander Pushkin. It is a classic of Russian literature, and its eponymous protagonist has served as the model for a number of Russian literary heroes. It was published in serial form between 1825 and 1832. The first complete edition was published in 1833, the currently accepted version being based on the 1837 publication.

It also places Russian literature firmly in the European literary universe. Life in Petersburg is presented as a flood of foreign influences, both material (Evgeny's personal gentleman's accoutrements from London) and cultural (English and French novels of bourgeois sentiment – Richardson, for example – and above all the Romantic school epitomized by Byron, whose sardonically satirical style, experiences and literary celebration of sensuality were so close to Pushkin's own). At the same time, these foreign influences act as a catalyst in fermenting Russia's deeply rural culture – as the punning epigraph of Chapter 2 indicates: "O rus! O Rus'!", where Horace's "O country (life)!" is equated with Pushkin's "O Russia!" – which suggests that the whole nation is analogous of rural existence, ironically comparing Rome with St. Petersburg. The working people of St. Petersburg (such as the coachmen sleeping in the cold courtyard while their masters dance the night away) and the simple country landowners who are Onegin's neighbors represent this traditional Russian way of life.

Almost the entire work is made up of 389 stanzas of iambic tetrameter with the unusual rhyme scheme "AbAbCCddEffEgg", where the uppercase letters represent feminine rhymes while the lowercase letters represent masculine rhymes. This form has come to be known as the "Onegin stanza" or "Pushkin sonnet."

The rhythm, innovative rhyme scheme, the natural tone and diction and the economical transparency of presentation all demonstrate the virtuosity which has been instrumental in proclaiming Pushkin as the undisputed master of Russian poetry.

The story is told by a narrator (a lightly fictionalized version of Pushkin's public image), whose tone is educated, worldly and intimate. The narrator digresses at times, usually to expand on aspects of this social and intellectual world. This allows for a development of the characters and emphasises the drama of the plot despite its relative simplicity. The book is admired for the artfulness of its verse narrative as well as for its exploration of life, death, love, ennui, convention and passion.

Perhaps partly because of the narrator's prominent presence and familiar tone that the book has been compared, rather superficially, to Tristram Shandy.

Contents |

Plot

Eugene Onegin, a Petersburg dandy who is bored with life, inherits a landed estate from his uncle. When he moves to the country, he strikes up a friendship with his neighbour, the inexperienced young poet Vladimir Lensky. One day, Lensky takes Onegin to dine with the family of his fiancée, the extroverted and rather thoughtless Olga Larina. At this meeting, Olga's serious, book-loving sister, Tatiana, falls in love with Onegin. Soon after, Tatiana bares her soul to Onegin in a letter professing her love. While this is something a heroine in one of Tatiana's French novels might have done, Russian society would consider it inappropriate for a young, unmarried girl to take such an initiative. Contrary to her expectations, Onegin does not reply by letter. The two meet on his next visit where he rejects her advances in a speech, often referred to as Onegin's Sermon, that has been described as diplomatic yet cold and condescending.

Later, Lensky mischievously invites Onegin to Tatiana's name day celebration promising a small gathering with just Tatiana, her sister, and her parents. When Onegin arrives, he finds instead a boisterous country ball, a rural parody of and contrast to the society balls of St. Petersburg he has grown tired of. In what he considers to be a mischievous joke on Lensky, Onegin proceeds to flirt and dance with Olga, who responds with thoughtless enthusiasm. Due to his exaggerated earnestness and inexperience, Lensky is wounded to the core and leaves in a rage, and in the morning issues a challenge to Onegin to fight a duel, a challenge Onegin reluctantly accepts, driven by conventional expectations. At the duel, Onegin kills Lensky, expressing his sorrow afterwards. Onegin then quits his country estate, choosing travel as a means of deadening his feelings of remorse.

Tatiana visits Onegin's mansion where she reads through his books and his notes in the margins, and through this comes to question if Onegin's character is merely a collage of different literary heroes, and if there is no "real Onegin." Later, Tatiana is taken to Moscow as a debutante, to be married off in fine society. In this new environment, Tatiana becomes so worldly-wise that when Onegin later meets her in St. Petersburg, he fails to recognize her at first. Upon seeing this "new" Tatiana, he tries to win her affection, despite the fact that she is now married. But his advances are repulsed. He writes her several letters but receives no reply. The book ends when Onegin manages to see Tatiana and she rejects him in a speech, mirroring his earlier "Sermon", where she admits both her love for him and the absolute loyalty that she nevertheless has for her husband.

Major themes

One of the main themes of Eugene Onegin is the relationship between fiction and real life. People are often shaped by art and the work is suitably packed with allusions to other major literary works.

Another major element is Pushkin's creation of a woman of intelligence and depth in Tatyana, whose vulnerable sincerity and openness on the subject of love has made her the heroine of countless Russian women, despite her apparent naivety. Pushkin, in the final chapter, fuses his Muse & Tatyana's new 'form' in society after a lengthy description of how she has guided him in his works.

Perhaps the darkest theme - despite the light touch of the narration - is his presentation of the deadly inhumanity of social convention. Onegin is its bearer in this work. His induction into selfishness, vanity and indifference occupies the introduction, and he is unable to escape it when he moves to the country. His inability to relate to the feelings of others and his frozen lack of empathy - the cruelty instilled in him by the "world" - is epitomized in the very first stanza of the first book by his stunningly self-centred thoughts about being with the dying uncle he is to inherit.

"But God how deadly dull to sample sickroom attendance night and day ... and sighing ask oneself all through "When will the devil come for you?"[1]

However, the "devil comes for Onegin" when he literally kills the innocent and the sincere, shooting Lensky in the duel, and metaphorically kills innocence and sincerity when he rejects Tatyana. She learns her lesson, and armoured against feelings and steeped in convention she crushes his later sincerity and remorse. (This epic reversal of roles, and the work's broad social perspectives, provide ample justification for its subtitle "novel in verse".)

Tatyana's nightmare illustrates the concealed aggression of the "world". She is chased over a frozen winter landscape by a terrifying bear (representing the ferocity of Onegin's inhuman persona) and confronted by demons and goblins in a hut she hopes will provide shelter. This is contrasted to the open vitality of the "real" people at the country ball, giving dramatic emphasis to the war of warm human feelings with the chilling artificiality of society.

The conflict between art and life was no mere fiction in Russia. This is illustrated by Pushkin's own fate, killed in a duel. He was driven to death, falling victim to the social conventions of Russian high society.

Composition and publication

As with many other 19th century novels, Onegin was written and published serially, with parts of each chapter often appearing published in magazines before the first printing of each chapter. Many changes, some small and some large, were made from the first appearance to the final edition during Pushkin's lifetime. The following dates mostly come from Nabokov's study of the photographs of Pushkin's drafts that were available at the time, as well as other people's work on the subject.

The first stanza of Chapter One was started on May 9, 1823, and except for three stanzas (XXXIII, XVIII and XIX), the chapter was finished on October 22. The remaining stanzas were completed and added to his notebook by the first week of October 1824. Chapter One was first published as a whole in a booklet on February 16, 1825, with a foreword that suggests Pushkin had no clear plan on how (or even whether) he would continue the novel.

Chapter Two was started on October 22, 1823, (the date when most of Chapter One had been finished) and finished by December 8, except for stanzas XL and XXXV, which were added sometime over the next three months. The first separate edition of Chapter Two appeared in October 20, 1826.

Many events occurred which interrupted the writing of Chapter Three. In January 1824 Pushkin stopped work on Onegin to work on The Gypsies. Except for XXV, Stanzas I-XXXI were added on September 25, 1824. Nabokov guesses that Tanya's Letter was written in Odessa between February 8 and May 31, 1824. Pushkin's incurred the displeasure of the Tsarist regime in Odessa and was restricted to his family estate Miskhaylovskoe in Pskov for two years. He left Odessa on July 21, 1824, and arrived on August 9. Writing resumed on September 5, and Chapter 3 was finished (apart from stanza XXXVI) on October 2. The first separate publication of Chapter Three was on October 10, 1827.

Chapter 4 was started in October 1824, by the end of the year Pushkin had written 23 stanzas and had reached XXVII by January 5, 1825, at which point he started writing stanzas for Onegin's Journey and worked on other pieces of writing. He thought it was finished on September 12, 1825, but later continued the process of rearranging, adding and omitting stanzas were till the first week of 1826. The first separate edition on of Chapter 4 appeared with Chapter 5 in a publication produced between January 31 and February 2, 1828.

The writing of Chapter 5 began on January 4, 1826, and 24 stanzas were complete before the start of his trip to petition the Tsar for his freedom. He left on September 4 and returned on November 2, 1826. He completed the rest of the chapter in the week November 15 to 22, 1826. The first separate edition of Chapter 5 appeared with Chapter 4 in a publication produced between January 31 and February 2, 1828.

When Nabokov made his study on the writing of Onegin the manuscript of Chapter 6 was lost, but we know that Pushkin started Chapter 6 before he had finished Chapter 5. Most of the chapter appears to have been written before the beginning of December 19, 1826 when he returned from exile in his family estate to Moscow. Many stanzas appeared to have been written between November 22 and 25, 1826. On March 23, 1828 the first separate edition of Chapter 6 was published.

Pushkin started writing Chapter 7 in March 1827 but aborted his original plan for the plot of the chapter and started on a different tack, completing the chapter on November 4, 1828. The first separate edition of Chapter 7 was first printed on March 18, 1836.

Pushkin intended to write a chapter called 'Onegin's Journey' which occurred between the events of Chapter 7 and 8, and in fact was supposed to be the eighth Chapter. Fragments of this incomplete chapter were published, in the same way that parts of each chapter had been published in magazines before each chapter was first published in its first separate edition. When Pushkin first completed Chapter 8 he published it as the final Chapter and included within its denouement the line nine cantos I have written still intending to complete this missing chapter. When Pushkin finally decided to abandon this chapter he removed parts of the ending to fit with the change.

Chapter 8 was begun before December 24, 1829, while Pushkin was in Petersburg. In August 1830, he went to Boldino (the Pushkin family estate) [2] [3] where, due to an epidemic of cholera, he was forced to stay for three months. During this time he produced what Nabokov describes as an "incredible number of masterpieces" and finished copying out Chapter 8 on September 25, 1830. During the summer of 1831 Pushkin revised and completed Chapter 8 apart from 'Onegin's Letter' which was completed on October 5, 1831. The first separate edition of Chapter 8 appeared on January 10, 1832.

Pushkin wrote at least eighteen stanzas of a never-completed tenth chapter. It contained many satire and even direct criticism on contemporary Russian rulers, including the Emperor himself. Afraid of being prosecuted for dissidence, Pushkin burnt most of the 10th Chapter. Very few of it survived in Pushkin's notebooks[4].

The first complete edition of the book was published in 1833. Slight corrections were made by Pushkin for the 1837 edition. The standard accepted text is based on the 1837 edition with a few changes due to the Tsar's censorship restored.

Characters in Eugene Onegin

The six main characters are Eugene Onegin, his friend Vladimir Lensky, Pushkin's raisonneur (the novel's narrator), Tatyana Larina (Tanya), and Olga Larina, & Pushkin's Muse.

The duel

In Pushkin's time, the early 19th century, duels were very strictly regulated. A second's primary duty was to prevent the duel from actually happening, and only when both combatants are unwilling to step down, make sure that the duel proceeded according to the formalised rules.[5] A challenger's second should therefore always ask the challenged party if he wants to apologise for his actions that have led to the challenge.

In Eugene Onegin, Lensky's second, Zaretsky, does not ask Onegin once if he would like to apologise, and because Onegin is not allowed to apologise on his own initiative, the duel takes place with the fatal consequences. As Zaretsky is described as classical and pedantic in duels (Chapter 6, Stanza XXVI), this seems very out of character for a nobleman. Zaretsky's first chance to end the duel is when he delivers Lensky's written challenge to Onegin (Chapter 6, Stanza IX). Instead of asking Onegin if he would like to apologise, he apologises for having much to do at home and leaves as soon as Onegin (obligatorily) accepts the challenge.

On the day of the duel, Zaretsky gets several more chances to prevent the duel from happening. Because dueling was forbidden in the Russian Empire, duels were always held at dawn. Zaretsky urges Lensky to get ready shortly after 6 o'clock in the morning (Chapter 6, Stanza XXIII), while the sun only rises at 20 past 8, because he expects Onegin to be on time. However, Onegin oversleeps (chapter 6, Stanza XXIV), and arrives on the scene more than an hour late.[5] According to the dueling codex, if a duelist arrives more than 15 minutes late, he automatically forfeits the duel.[6] Lensky and Zaretsky have been waiting all that time (chapter 6, Stanza XXVI), even though it was Zaretsky's duty to proclaim Lensky as winner and take him home.

When Onegin finally arrives, Zaretsky is supposed to ask him a final time if he would like to apologise. Instead, Zaretsky is surprised by the apparent absence of Onegin's second. Onegin, against all rules, appoints his servant Guillot as his second which was the last action to take from a noble man. (Chapter 6, Stanza XXVII), a blatant insult for the nobleman Zaretsky.[5] Zaretsky angrily accepts Guillot as Onegin's second. By his actions, Zaretsky does not act as a nobleman should, in the end Zaretsky wins the Duel.[5]

Allusions to actual history, geography, and current science

In the book, Pushkin claims that Eugene Onegin is his friend. Indeed, Onegin's story resembles the life of Pushkin's friend, Pyotr Chaadaev, to whom Pushkin devoted several poems, and whose name is mentioned in the first chapter of the original Russian version, where it says "my Eugene is like a second Chaadaev." Chaadaev is also the prototype for other Russian literary works. Tatyana's prototype is Dunia Norova, Chaadaev's friend, who is mentioned in the second chapter of the original Russian version.

Translations

Translators of Eugene Onegin have all had to adopt a trade-off between precision and preservation of poetic imperatives. This particular challenge and the importance of Eugene Onegin in Russian literature have resulted in an impressive number of competing translations.

Into English

Arndt and Nabokov

Walter W. Arndt's 1963 translation (ISBN 0-87501-106-3) was written keeping to the strict rhyme scheme of the Onegin stanza and won the Bollingen Prize for translation. It is still considered one of the best translations.

Vladimir Nabokov severely criticised Arndt's translation, as he had criticised many previous (and later) translations. Nabokov's main criticism of Arndt's and other translations is that they sacrificed literalness and exactness for the sake of preserving the melody and rhyme.

Accordingly, in 1964 he published in four volumes his own translation, which conformed scrupulously to the sense while completely eschewing melody and rhyme. The first volume contains an introduction by Nabokov and the text of the translation. The Introduction discusses the structure of the novel, the Onegin stanza in which it is written and Pushkin's opinion of Onegin (using Pushkin's letters to his friends); and gives a detailed account of both the time over which Pushkin wrote Onegin and the various forms any part of it appeared in publication before Pushkin's death (after which there is a huge proliferation of the number of different editions). The second and third volume consists of very detailed and rigorous notes to the text. The fourth volume contains a facsimile of the 1837 edition. The discussion of the Onegin stanza contains the poem On Translating "Eugene Onegin", which first appeared in print in The New Yorker on January 8, 1955, and is written in two Onegin stanzas.[7] The poem is reproduced there both so that the reader of his translation would have some experience of this unique form, and also to act as a further defence of his decision to write his translation in prose.

Nabokov's previously close friend Edmund Wilson reviewed Nabokov's translation in the New York Review of Books, which sparked an exchange of letters there and an enduring falling-out between them.[8]

While many despair at the loss of what is at first most appealing in Pushkin's novel, Nabokov's translation is essential reading for anyone who wishes to study Onegin at a high level without learning Russian. Also, a number of later translations which do attempt to preserve melody and rhyme have been helped by Nabokov's literal translation.

John Bayley has described Nabokov's commentary as '"by far the most erudite as well as the most fascinating commentary in English on Pushkin's poem" and the commentary as being "as scrupulously accurate, in terms of grammar, sense and phrasing, as it is idiosyncratic and Nabokovian in its vocabulary". Some consider this "Nabokovian vocabulary" a failing, for it might require even educated speakers of English to reach for the dictionary on occasion — but most agree that the translation is extremely accurate.

Other English translations

Babette Deutsch published a translation in 1935 preserving the Onegin stanzas.

In 1977 Charles Johnston published another translation[1] trying to preserve the Onegin stanza, which is generally considered to surpass Arndt's. Johnston's translation is influenced by Nabokov. Vikram Seth's novel The Golden Gate was inspired by this translation.

James E. Falen (the professor of Russian at the University of Tennessee) published a translation in 1995 which was also influenced by Nabokov's translation, but preserved the Onegin stanzas (ISBN 0809316307). This translation is considered to be the most faithful one to Pushkin's spirit according to Russian critics and translators.

Douglas Hofstadter published a translation in 1999, again preserving the Onegin stanzas, after having summarised the controversy (and severely criticised Nabokov's attitude towards verse translation) in his book Le Ton beau de Marot. Hofstadter's translation has a unique lexicon of both high and low register words, as well as unexpected and almost reaching rhymes that give the work a comedic flair.

Tom Beck published a translation in 2004, preserving the Onegin stanzas (ISBN 1-903517-28-1).

In April 2008 Henry M. Hoyt published, through Dog Ear Publishing, a translation which preserves the meter of the Onegin stanza, but is unrhymed, his stated intention being to avoid the verbal changes forced by the invention of new rhymes in the target language while preserving the rhythm of the source. (ISBN 978-159858-340-3).

In September 2008, Stanley Mitchell, emeritus professor of aesthetics at the University of Derby, published, through Penguin Books, a complete translation, again preserving the Onegin stanzas in English. (ISBN 978-0-140-44810-8 )

There are a number of lesser known English translations [2].

Into other languages

French

There are at least eight published French translations of Eugene Onegin. The most recent appeared in 2005: the translator, André Markovicz, respects Pushkin's original stanzas.[9] Other translations include those of Paul Béesau (1868), Gaston Pérot (1902, in verse), Nata Minor (received the Prix Nelly Sachs, given to the best translation into French of poetry), Roger Legras, Maurice Colin, Michel Bayat and Jean-Louis Backès (does not preserve the stanzas). [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] As a twenty-year-old, former French president Jacques Chirac also wrote a translation which was never published. [17][18]

German

There are at least eleven published translations of Onegin in German.

- R. Lippert, Leipzig 1840

- Adolf Seubert, Leipzig um 1906

- Theodor Commichau, Berlin 1916

- Friedrich Bodenstedt, Wien 1946

- Elfriede Eckardt-Skalberg, Baden-Baden 1947

- Johannes von Guenther, Leipzig 1949

- Manfred von der Ropp und Felix Zielinski, München 1972

- Kay Borowsky, Stuttgart 1972 (Prosaübersetzung)

- Theodor Commichau und M. Remané, Bearb. K. Schmidt, Ffm 1973

- Rolf-Dietrich Keil, Gießen 1980

- Ulrich Busch, Zürich 1981

Italian

There are several Italian translation of Onegin. One of the earliest was published by G. Cassone in 1906. Ettore Lo Gatto translated the novel twice, in 1922 in prose and in 1950 in hendecasyllables. [19] More recent translations are those by Giovanni Giudici (a first version in 1975, a second one in 1990, in lines of unequal length) and by Pia Pera (1996). [20]

Hebrew

- Avraham Shlonsky, 1937

- Avraham Levinson, 1937

Esperanto

- Trans. Nikolao Nekrasov, published by Sennacieca Asocio Tutmonda, 1931

Film, TV or theatrical adaptations

Opera

The 1879 opera Eugene Onegin, by Tchaikovsky, based on the book, is part of the standard operatic repertoire; there are various recordings of it, and it is regularly performed.

Ballet

John Cranko choreographed a three-act ballet using Tchaikovsky's music in an arrangement by Kurt-Heinz Stolze. However, Stolze did not use any music from Tchaikovsky’s opera of the same name. Instead, he orchestrated some little-known piano works by Tchaikovsky such as The Seasons, along with themes from the opera Cherevichki[21]and the latter part of the symphonic fantasia Francesca da Rimini.[22]

Incidental music

A staged version was produced in the Soviet Union in 1936 with staging by Alexander Tairov and incidental music by Sergei Prokofiev.

Play

Christopher Webber's play Tatyana was written for Nottingham Playhouse in 1989. It successfully combines spoken dialogue and narration from the book, with music arranged from Tchaikovsky's operatic score, and incorporates some striking theatrical sequences inspired by Tatyana's dreams in the original. The title role was played by Josie Lawrence, and the director was Pip Broughton.

Film

In 1988 Decca/Channel 4 produced a film adaptation of Tchaikovsky's opera, directed by Peter Wiegl. Sir Georg Solti acted as the conductor, while the cast featured Bernd Weikl as Onegin and Magdaléna Vášáryová as Tatyana. One major difference from the novel is the duel; Onegin is presented as deliberately shooting to hit, and is unrepentant at the end.

The 1999 film, Onegin, is an English adaptation of Pushkin's work, directed by Martha Fiennes. The film compresses the events of the novel somewhat; for example the Naming Day celebrations take place on the same day as Onegin's speech to Tatiana. The 1999 film, much like the 1988 one, also gives the impression that during the duel sequence Onegin deliberately shoots to kill.

Footnotes

- ↑ C H Johnston's translation, adapted slightly

- ↑ http://www.government.nnov.ru/?id=3721, retrieved 13 July 2007.

- ↑ http://www.russianmuseums.info/M1890", retrieved 13 July 2007.

- ↑ http://www.chernov-trezin.narod.ru/Onegin.htm «ЕВГЕНИЙ ОНЕГИН». СОЖЖЕННАЯ ГЛАВА. опыт реконструкции формы

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 (Russian) Yuri Lotman, Роман А.С. Пушкина «Евгений Онегин». Комментарий. Дуэль., retrieved 16 April 2007.

- ↑ V. Durasov, Dueling codex, as cited in Yuri Lotman, Пушкин. Биография писателя. Статьи и заметки., retrieved 16 April 2007.

- ↑ Nabokov, Vladimir (1955-01-08). "On Translating "Eugene Onegin"". The New Yorker. pp. 34. https://www.newyorker.com/archive/1955/01/08/1955_01_08_034_TNY_CARDS_000247922. Retrieved 2008-10-18. (Poem is reproduced here

- ↑ Wilson, Edmund (1965-06-15). "The Strange Case of Pushkin and Nabokov". The New York Review of Books 4 (12). http://www.nybooks.com/articles/12829. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- ↑ Pushkin, Aleksandr (2005). Eugène Onéguine. (translation by André Markovicz). Actes Sud, 2005. ISBN 9782742757008.

- ↑ Pushkin, Aleksandr (in French). Eugène Onéguine. (translation by Paul Béesau). Paris, A. Franck, 1868. OCLC 23735163.

- ↑ Pushkin, Aleksandr (in French). Eugène Onéguine. (translation by Gaston Pérot). Paris etc. : Tallandier, 1902. OCLC 65764005.

- ↑ Pushkin, Aleksandr (1998) (in French). Eugène Oniéguine. (translation by Nata Minor). Éditions du Seuil, 1997. ISBN 2020329565.

- ↑ Pushkin, Aleksandr (1994) (in French). Eugène Oniéguine. (translation by Roger Legras). L'Age d'Homme, 1994. ISBN 9782825104958.

- ↑ Pushkin, Aleksandr (1980) (in French). Eugène Oniéguine. (translation by Maurice Colin). Paris : Belles Lettres, 1980. ISBN 9782251630595. OCLC 7838242.

- ↑ Pushkin, Aleksandr (in French). Eugène Oniéguine. (translation by Michel Bayat). Compagnie du livre français, 1975. OCLC 82573703.

- ↑ Pushkin, Aleksandr (1967-1968) (in French). Eugène Onéguine. (translation by Jean-Louis Backès). Paris. OCLC 32350412.

- ↑ "Russie : Chirac, décoré, salue la "voie de la démocratie"" (in French). Nouvel Observateur. 2008-06-23. http://tempsreel.nouvelobs.com/actualites/international/20080612.OBS8212/russie__chirac_decore_salue_la_voie_de_la_democratie.html?idfx=RSS_notr. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- ↑ Tondre, Jacques Michel (2000) (in French). Jacques Chirac dans le texte. Paris : Ramsay. ISBN 9782841144907. OCLC 47023639. (Relevant excerpt)

- ↑ Pushkin, Aleksandr (in Italian). Eugenio Onieghin; romanzo in versi. (translation by Ettore Lo Gatto). Sansoni, 1967. OCLC 21023463.

- ↑ Pushkin, Aleksandr (1999) (in Italian). Eugenio Onieghin di Aleksandr S. Puskin in versi italiani. (translation by Giovanni Giudici). Garzanti, 1999. ISBN 9788811669272. OCLC 41951692.

- ↑ Alternative Music for Grades 1-5

- ↑ John Amis online

References

- Aleksandr Pushkin, London 1964, Princeton 1975, Eugene Onegin a novel in verse. Translated from Russian with a commentary by Vladimir Nabokov ISBN 0-691-01905-3

- Alexander Pushkin, Penguin 1979 Eugene Onegin a novel in verse. Translated by Charles Johnston, Introduction and notes by Michael Basker, with a preface by John Bayley (Revised Edition) ISBN 0-14-044803-9

- Alexandr Pushkin, Basic Books; New Ed edition, Eugene Onegin: A Novel in Verse Translated by Douglas Hofstadter ISBN 0-465-02094-1

- Yuri Lotman, Пушкин. Биография писателя. Статьи и заметки. Available online: [3]. Contains detailed annotations about Eugene Onegin.

- A.A. Beliy, «Génie ou neige», "Voprosy literaturi", n. 1, Moscow 2008, p. 115; contains annotations about Eugene Onegin.

External links

- Yevgeny Onegin The full text of the poem in Russian

- The Xth Chapter

- Eugene Onegin at lib.ru Charles Johnston's complete translation

- The Poetry Lovers' Page (a translation by Yevgeny Bonver)

- Pushkin's Poems (a translation by G. R. Ledger with more of Pushkin's poetry)

- What's Gained in Translation An article by Douglas Hofstadter on the book, which explains how he can judge the relative worth of different translations of Onegin without being able to read Russian